5 Ways to Use Open Data in Agriculture

Have you ever thought about using open data for food and agriculture? Let’s take a trip around the world to look at innovative data-driven agriculture projects in different countries - you might be surprised at the various innovative ways we rely on data in the agricultural value chain, from the farm to your table.

It goes by many names – smart farming, e-agriculture, digital farming, agriculture 4.0 (soon 5.0!) – but in the end they all refer to the same thing: data-driven agriculture. Refresh your old-fashioned stereotypes about low-tech farming: Today, data support farmers all along the cultivation process, from land purchase to plantation, harvest, and commercialization.

Geospatial data, for example, allow farmers to spot the most fertile plots of land and to selectively drop pesticides, while weather and price data help farmers choose the most profitable crops to plant in a certain season. Soil data inform decisions on the type and amount of fertilizer to be used, while sensor data allow monitoring plants and livestock’s growth and health. Last but not least, food item data can track products from farm to table.

Open data is part of this broader trend, with farming-related datasets becoming increasingly common in national open data portals. Argentina, for instance, publishes data on everything from meat production to biomass consumption and draught incidence. India provides data on producer support schemes, farmers’ queries to call centers and the funding status of research projects. Botswana makes statistics on arable land, fertilizer consumption and pesticide trade publicly available. But what are the use cases of open data in agriculture? Here are 5 examples from across the world!

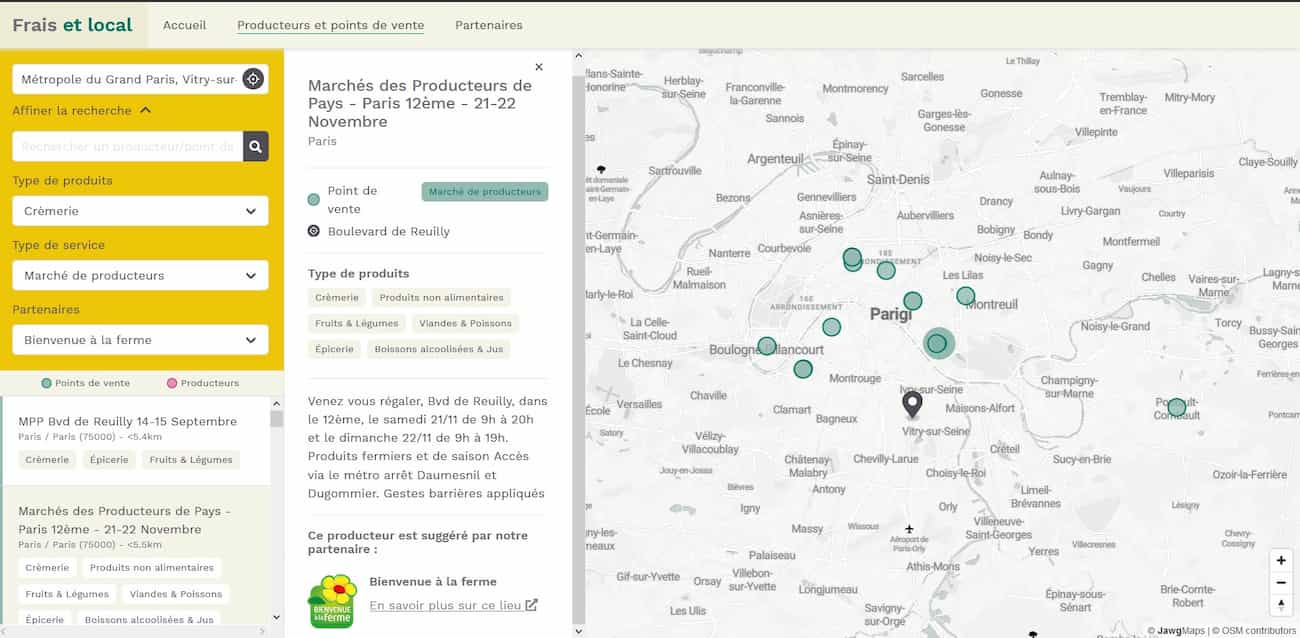

France: Open Data for Local Producers

As the Covid-19 pandemic exposes the fragility of international supply chains, France has found a way to boost domestic consumption while promoting “healthy and responsible” living. The Frais et Local (literally “fresh and local”) open data portal helps consumers find the closest local producers of farm products, including fruit, vegetables, meat, fish, dairy, juices, and alcoholic drinks, anywhere in France and its overseas territories. Users can search by product, type of sale point (farm, market, store, website) or consortium and choose among over 8,000 producers with the click of a button.

Similar initiatives also exist at the local level. The department of Haute-Garonne, in south-western France, has recently inaugurated DirectFermier31, an open data platform which gathers the location and contact information of over 300 direct producers and more than 600 points of sale around the city of Toulouse. The portal allows for very granular research thanks to advanced filters like “quality label” (IGP, AOP, etc..) and “distribution options” (delivery, drive-in, market…and, for aficionados, even hand picking!).

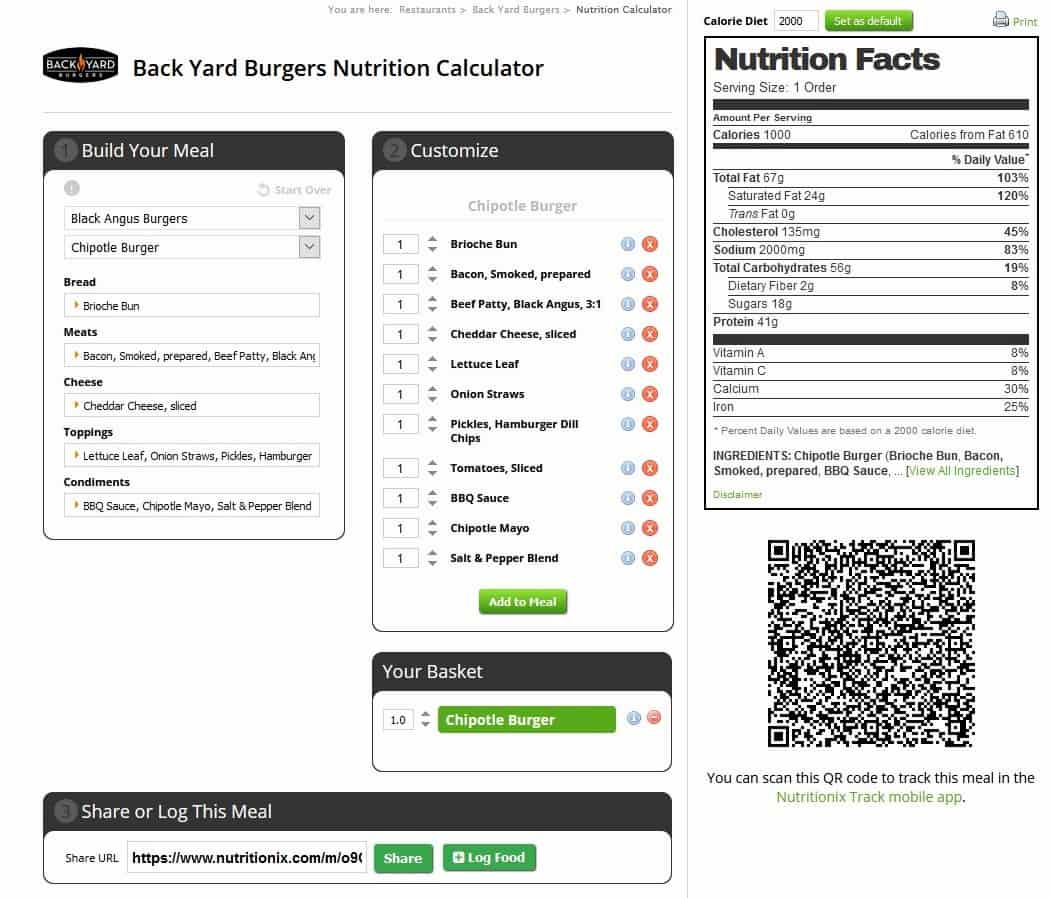

USA: Open Data for Nutritional Health

Obesity and other nutritional disorders have long been a top public health concern in the US. For this reason, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) collects nutritional data on raw, processed and even experimental food, and makes it freely available for reuse through one, centralized gateway. FoodData Central provides researchers, policymakers, nutritionists and health professionals with open data on everything from broccoli to lasagna, and with APIs to plug the data into third-party apps.

One such app is MyPlate. Developed by the USDA, MyPlate helps users follow the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025 by providing a personalized food plan and incentives to stick to it. The customized plan is based on the user’s age, sex, height, weight, and level of physical activity, while encouraging users with alerts, daily goals, challenges, and virtual prizes, as well as a vast and customizable recipe list. Another popular app is Nutritionix. Originally built solely on USDA open data, Nutrinionix has turned into a profitable business by integrating external databases, including restaurant menus and popular meals. Acclaimed by users trying to lose weight, Nutritionix helps you calculate daily recommended calories intake, keep track of food consumption, share the food log with an accredited trainer or dietitian, and consult nutritional facts on almost 1 million foods. Don’t feel overwhelmed by the size of the database: users can easily surf it by typing the name of the meal, scan its QR code or just speak to the app.

Copy to clipboard

Copy to clipboard

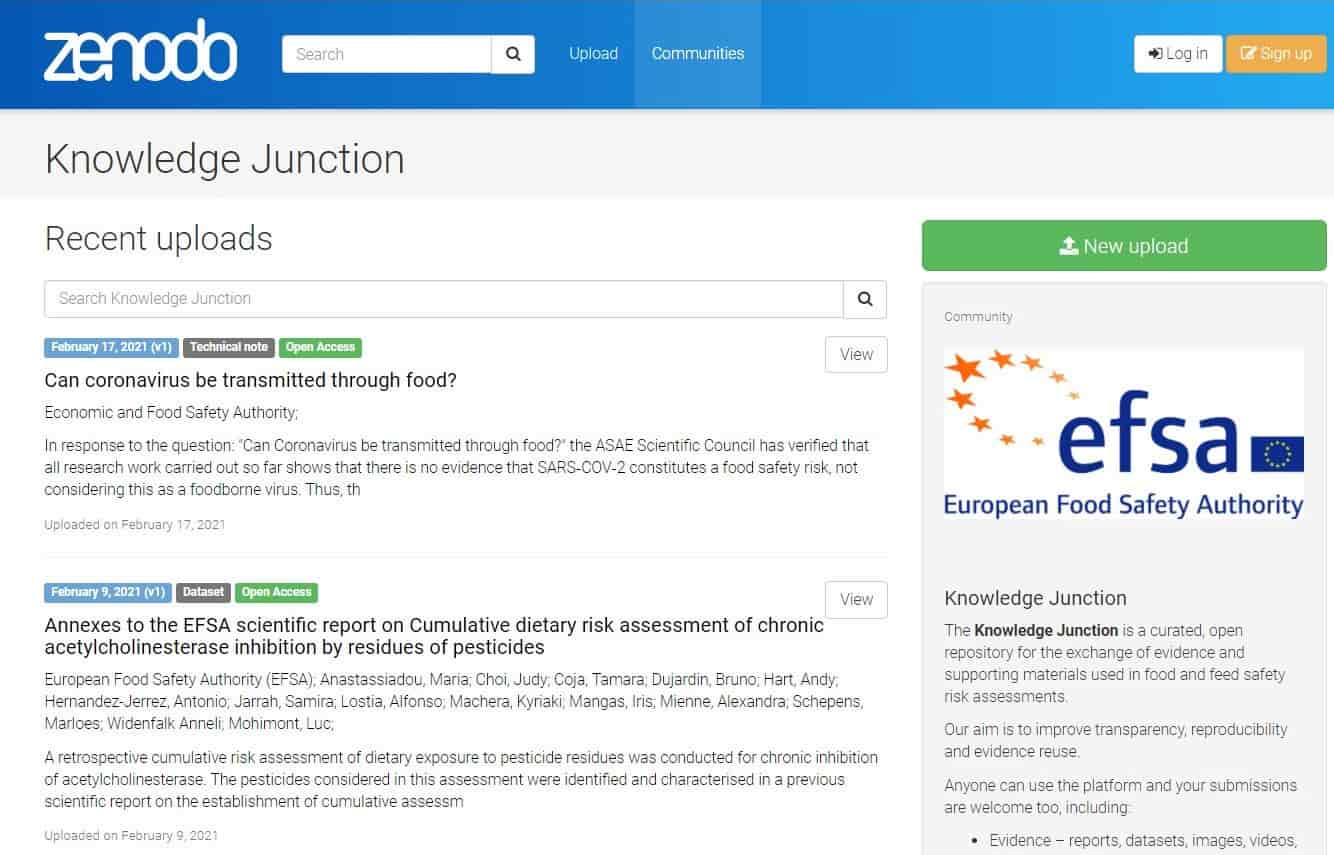

European Union: Open Data for Food Safety

Eating healthy is more than just adding veggies to your diet and keeping calories in check. It’s also about consuming products that don’t pose biological hazards (food- and animal-borne diseases like salmonella or swine flu, respectively), don’t contain chemical residues (like pesticides or veterinary medicines) and are not contaminated by natural or man-made substances, like lead or illegal food additives. In short, eating safely is the first step of eating healthy.

Ensuring that the food on your table meets the quality and safety standards is the mission of the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). And here comes the interesting part: to carry out its food and feed safety risk assessments, the EFSA engages in a sort of “reverse open data.” Instead of simply publishing information on the EU Open Data Portal, the agency also invites everyone to upload evidence, tools, documents, and any other relevant resource to inform EFSA’s food and feed safety investigations.

To share data with the agency, users simply have to register at Knowledge Junction, a community within the CERN-run open science platform Zenodo. The material (datasets, lab outputs, code, protocols, scientific papers- you name it!) undergoes a standardized quality check and… you are done! The data becomes freely available not only for the EFSA, but also for anyone else working on food and feed safety.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Open Data for Food Security

You are not seeing double: food security and food safety are not the same. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), food security means having at all times both physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food. This can be a challenge in regions like sub-Saharan Africa, where economic hardship, climate change, conflict and high population growth can quickly lead to food shortages. The Food Security Portal aims at preventing this type of crisis.

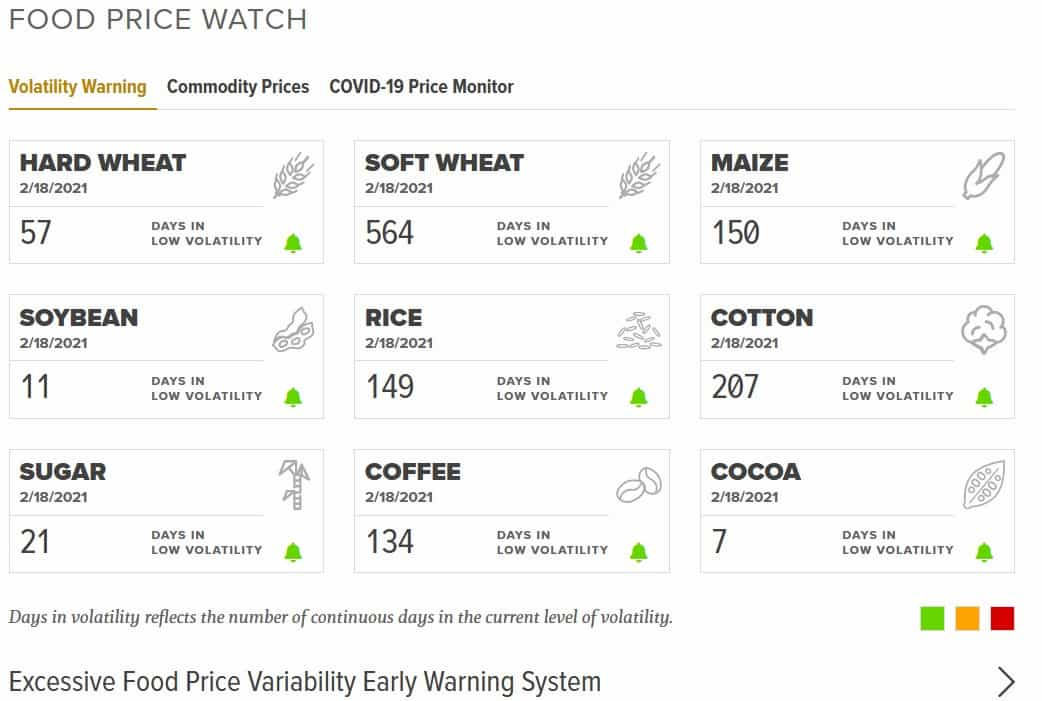

Run by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and financed by the European Commission, the Food Security Portal informs farmers, traders, and policymakers about the daily production level and price of agricultural commodities and issues warning when their volatility reaches worrying levels. The platform monitors commodities such as corn, rice, soybean, and cocoa, and makes over 12,000 datasets on price variability, media analysis and other food security indicators freely available for reuse.

Opening agricultural data alone is certainly not enough to eradicate food insecurity. For this reason, the Global Open Data for Agriculture and Nutrition initiative (GODAN) helps stakeholders in the Global South understand and reuse data, identify meaningful use cases, and set roadmaps to implement them. GODAN also provides methods, tools, and training to increase the supply, quality, and interoperability of data, facilitates coordination among existing projects and engages in high-level advocacy to raise public and private institutional support for open data.

Copy to clipboard

Copy to clipboard

Japan: Open Data for a Harmonious Farming Sector

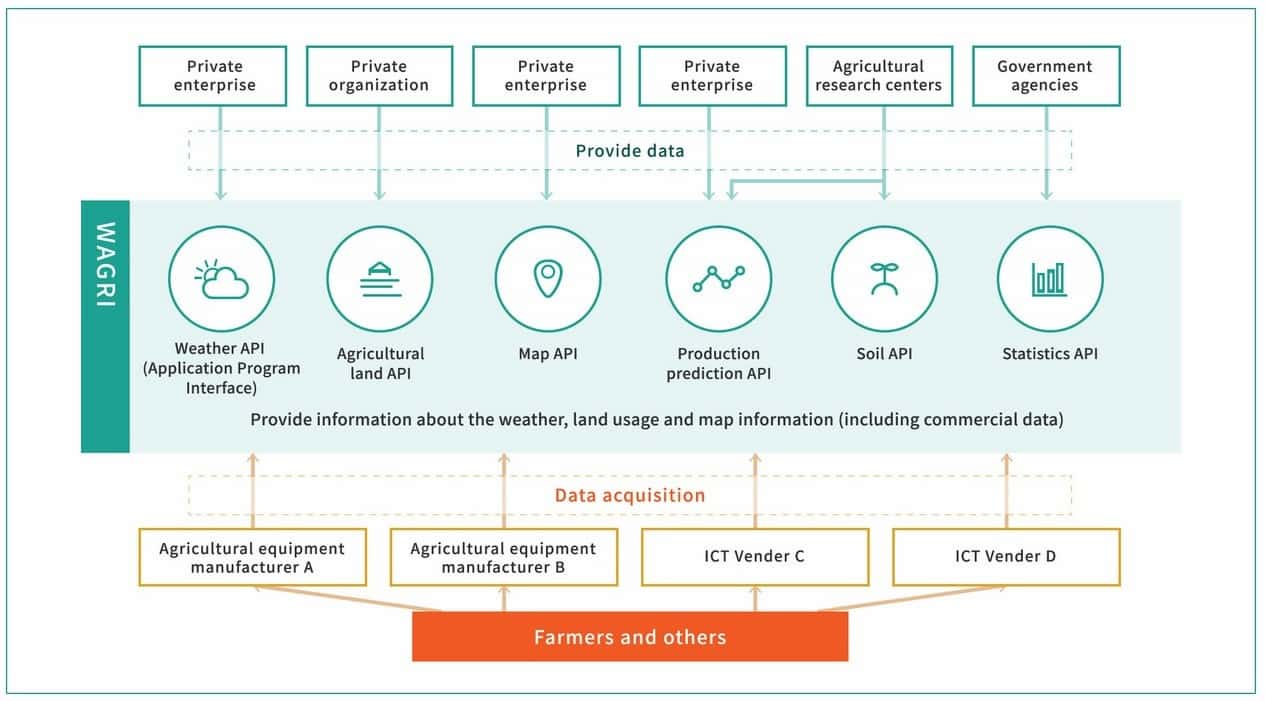

One of the greatest challenges to the massive adoption of open data in agriculture is the tension between public good and private interests. But a solution might already be available: WAGRI, Japan’s agricultural data collaboration platform. Named after wa (“harmony” in Japanese) and agri (for “agriculture”), WAGRI aims at harmonizing data formats used in the farming sector to facilitate data sharing among farmers, agribusinesses, software providers and equipment manufacturers.

What’s special about this platform is that in addition to open data, tools, and APIs freely provided by the Ministry of Agriculture and the National Agriculture Research Organization (NARO), WAGRI also makes data and software by private companies available for a fee. Among NARO-powered services is the “Growth and Yield” prediction tool. Another example of a private software is Hitachi’s soil management “GeoMation Agriculture Support Application.” Future applications may include an AI diagnosis tool for pests and diseases and a universal API compatible with equipment data from different vendors.

Thanks to its ability to align public and private interests, to develop a sustainable business model and to constantly provide new digital tools relevant to farmers’ everyday work, WAGRI could become a model for other data collaboration initiatives, like the upcoming Common European Agricultural Data Space.

To sum up, data are key to increase the productivity, profitability, and sustainability of agriculture, but their impact is limited when they remain siloed in different organizations. Opening farming data enables us to find new synergies among stakeholders in the food chain, and more importantly, to contribute to building healthier, safer, and more food secure societies.

Data Trends

Data Trends

How successful are governments at sharing their data with citizens and businesses? The latest Open Data Maturity report provides an overview of progress across Europe, and highlights the importance of improving data portals and measuring impact to future success