Everything you need to know about the data economy

On the first day of the Next Generation Internet Summit, one of the key topics on the agenda was the future of the data economy. Why does it matter today?

On the first day of the Next Generation Internet Summit, one of the key topics on the agenda was the future of the data economy. Why does it matter today?

Between 2011 and 2020, the volume of data in the world (the so-called datasphere) has increased from 1.8 to 59 zettabytes (1 ZB = 1 billion TB); in 2025, it is expected to reach an astonishing 175 ZB. The growing ubiquity of big data has fueled concerns about data privacy, leading to the introduction of data protection laws across the world (the GDPR in the EU, the CCPA in the US, the Personal Information Protection Law in China, the Act on the Protection of Personal Information in Japan, etc.). So, what do these dynamics mean? Researchers, innovators, and policymakers increasingly agree on one answer: our data economy needs new systems of (personal) data storage, management and sharing.

In this article I will take you through the latest developments in data economics debates, personal data management models and data sharing network architectures.

Grasping the nature of data

As it often happens in the digital sector, there is no universally agreed upon definition of data economy. My favorite is the one by Jani Koskinen, a researcher at the University of Turku, Finland: the data economy is an ecosystem of organizations for whom data is the main source or object of their business. There is even a related discipline: data economics. And one of the greatest challenges in this field is determining what kind of economic asset data are– as a famous journal put it, are data more like oil or sunlight?

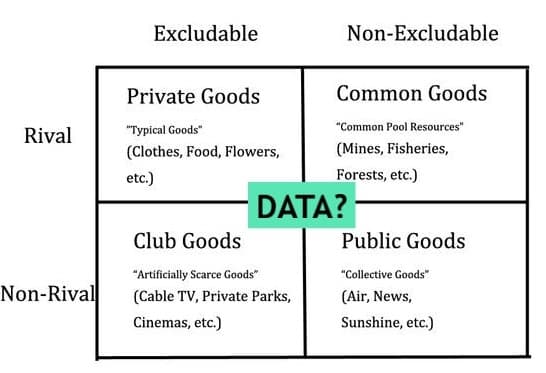

The very nature of data challenges the traditional classification in private, public, common pool or club goods. Data are in fact non-rival, that is, they can be copied, shared and reused infinite times by different people without decreasing in neither amount nor quality; at the same time, some data are strictly personal or confidential, so we’d prefer that they stay private. Data can be made accessible to some and excluded from others with methods like encryption, but they can also be made available to everyone in the form of open data. It seems therefore that different types of data fall in different categories.

Another challenge is that data, as pieces of information, are not valuable in themselves, but in the (re)uses we make of them: even if we wanted to evaluate data, their price would be subjective, as the same information might be worth different amounts to different people. At the same time, data is a valuable economic resource, underlying business models in sectors as diverse as agriculture, banking, and manufacturing. As I discuss in another blogpost, this has led the EU to conceive Data Spaces where businesses can share non-personal data among themselves and with governments, thus boosting economic growth, interoperability, and innovation. But what about personal data?

Inventing new ways to manage personal data

Personal data are as -if not even more- valuable as non-personal data for research institutions and businesses to develop, improve and give access to digital services and solutions, from social media to AI-based medical diagnoses. At the same time, the intimate nature of personal data demands special safeguards to protect privacy. To reconcile economic and legal requirements, personal data are increasingly considered not so much as goods, but as assets on which we exercise rights. How to manage this new asset class? Here are three interesting ideas.

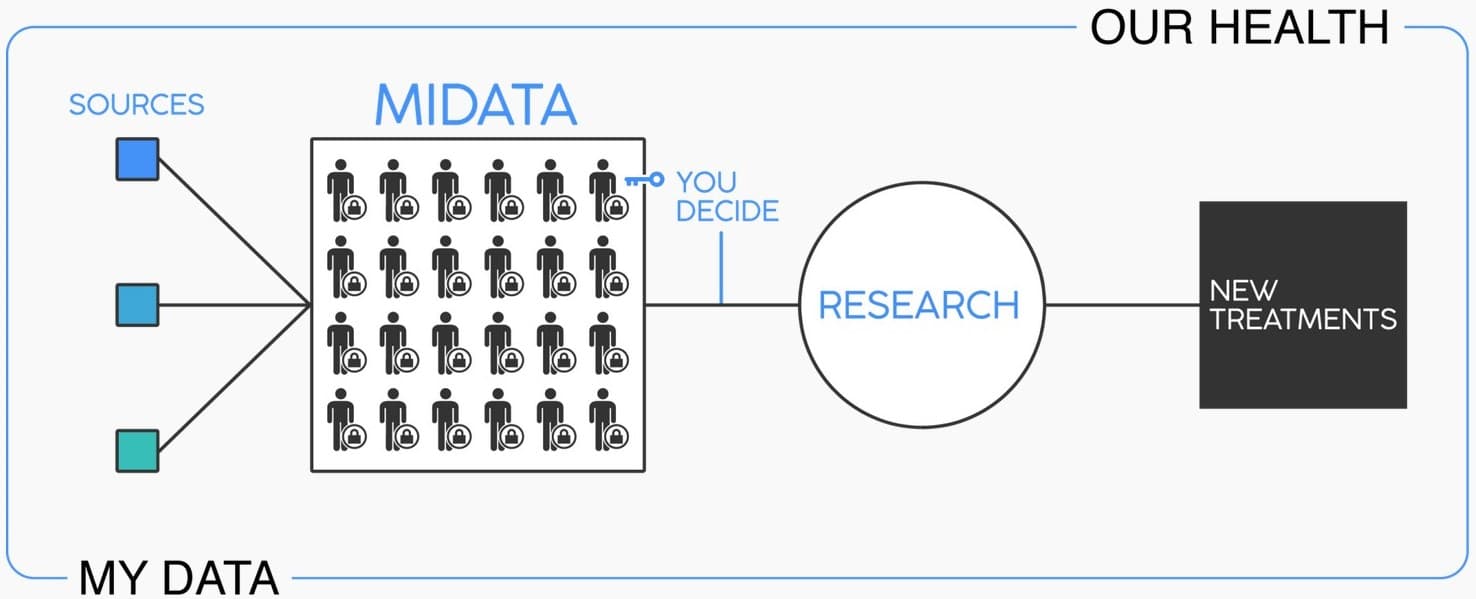

One option is data commons, a model by which individuals delegate the management of their personal data to a not-for-profit cooperative, whose members jointly decide which organizations to share data with, in line with the social cause the co-op is pursuing. A great example is the Swiss MIDATA cooperative, which collects the health data that its members and account holders decide to share, and gives access to that information to startups, IT providers and research centers offering data-driven health services or performing medical research and clinical trials.

A formal alternative to data commons is data trusts, legal entities that manage personal data on behalf of individuals according to the terms of the trusts, which are the equivalent of data co-ops’ social cause. Unlike commons, however, trusts may be public or private, and the trustees are professionals rather than volunteers. In addition, trustees have legal responsibilities (fiduciaries duties) to promote data subjects’ interests. This means that while they may be paid for their work, they can’t profit from it at the expense of data subjects. Data trusts are gaining attention especially in the UK, thanks to the work of organizations like the Open Data Institute and the Data Trusts Initiative.

Another idea – the one the EU is investing in – is self-sovereign identities (SSI). Often built on distributed ledger technologies (DLT) like blockchain, self-sovereign identities rely on encrypted data stores (a.k.a. wallets) gathering a person’s identity attributes and enabling individuals to decide, on a case by case basis, which piece of information to share and with whom, thus giving them full control over their data. Over the last five years, many small-scale SSI projects have been launched across the world- among the most famous and promising is the open source network Sovrin.

Building a fair data economy

Whatever personal data management model our societies will opt for, it will have to be embedded in the broader data ecosystem. Providing the governance framework and architectural requirements for that ecosystem is the mission of two ongoing European initiatives.

One is DECODE, an EU-funded project which developed a controlled and anonymous data sharing and identity attributes verification network linking citizens and local administrations. The architecture relies on blockchain technology and attribute-based cryptography and envisions the creation of city-level open data commons. The system was tested in Amsterdam and Barcelona to access a digital democracy platform, a local social network, and a municipal registry, as well as to anonymously share data from residential IoT sensors. More on the pilots is available here.

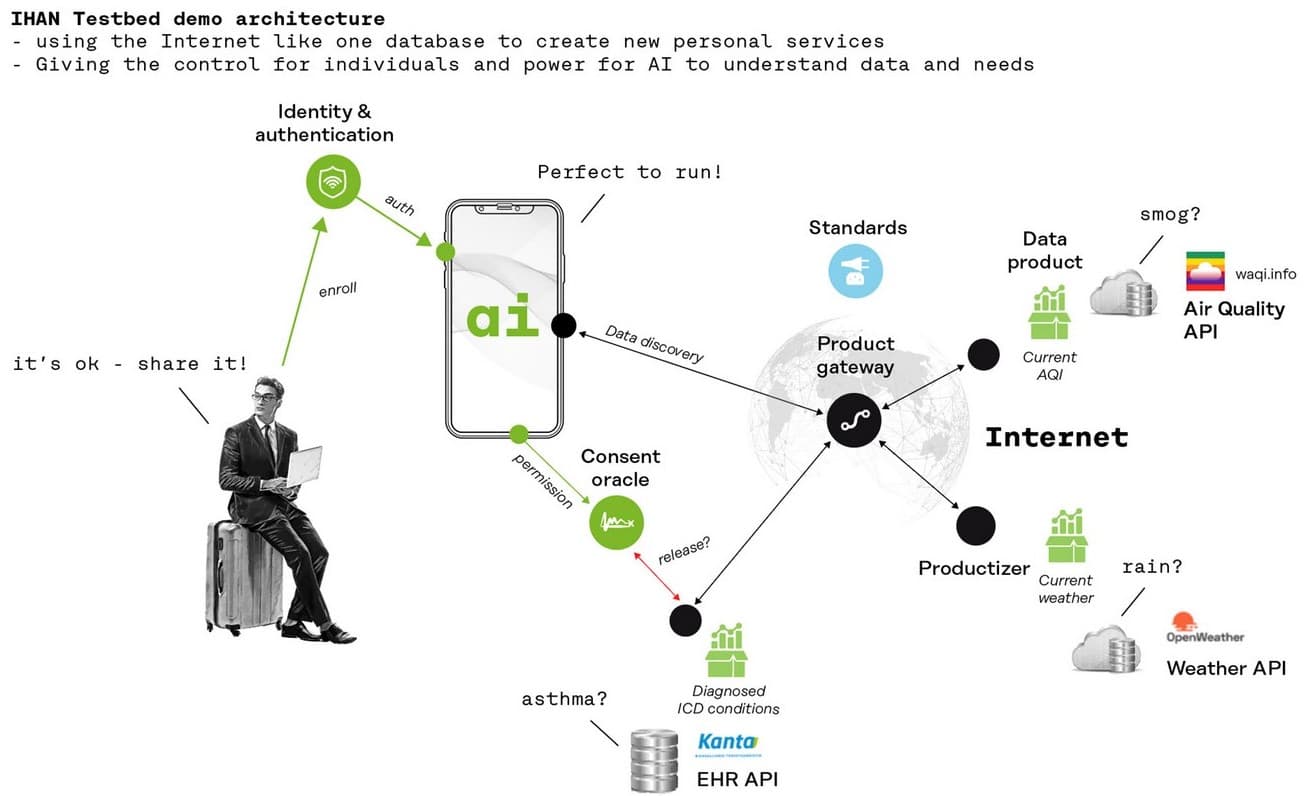

The other is IHAN, a project by the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra. IHAN provides a technical and governance framework for a “fair and human-driven data market”, where data flows freely and safely and is equally available to SMEs, large companies, and the public sector. The technical specifications of this architecture are available in the Blueprint 2.5, while sample data sharing agreements can be found in the Rulebook. By the end of the year, a testbed for entrepreneurs and developers to experiment with business models and applications based on IHAN fair standards and technologies will also be available.

It is too soon to say which theories, models and network architectures will prevail, but three things are clear: first, they will give rise to new, data-based business models; second, they will enable fairer and more intense data sharing; lastly, and maybe most importantly, they will empower individuals by giving them more control over their data and making them part and parcel of the data economy of tomorrow.

In an increasingly data-driven world, understanding the differences between data, metadata, data assets, and data products is essential to maximizing their potential. This is because these interrelated yet distinct concepts each play a key role in driving digital transformation by facilitating data sharing and consumption at scale.

Organizational silos prevent data sharing and collaboration, increasing risk and reducing efficiency and innovation. How can companies remove them and ensure that data flows seamlessly around the organization so that it can be used by every employee?